If you’ve visited our “Hype-Free Zone,” you know what we think of wildly exaggerated or even blatantly false claims about the supposed curative properties of certain types of fancy salt. We specifically mention Himalayan salt, simply because no other salt’s hype has infested the internet to such an extent. But just because a particular type of salt is nauseatingly hyped-up doesn’t mean the salt itself is no good or that there isn’t an interesting story behind it. Many people really like the flavor of Himalayan salt, and we think you’ll also enjoy reading its story.

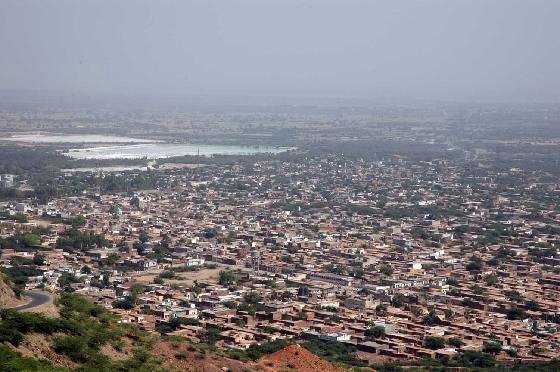

Himalayan salt doesn’t actually come from the Himalayas. It comes from the Khewra salt mine in Pakistan.

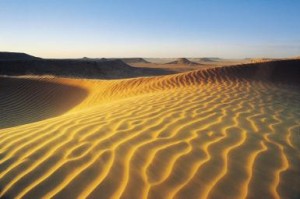

Of course, “Pakistani Salt” doesn’t conjure up quite the same majestic mental images as “Himalayan Salt.” Thus, the magic of marketing combined with the average consumer’s poor knowledge of Asian geography work in tandem to erase a gap of hundreds of miles between where something is said to come from and where it actually comes from. For our story, though, it’s quite fortuitous that the Khewra salt mine sits at a mere 1,000 ft elevation 100 miles south of Islamabad. Because if it actually was tucked in some inaccessible nook high in the Himalayas, it wouldn’t have such an interesting history.

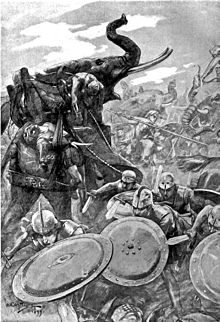

Going back 23+ centuries, Alexander the Great’s campaigns had come about as far eastward as they were going to get. He had just won a victory over Porus at the Jhelum River (better known by the Greek name, Hydaspes, among historians).

If you search for the Khewra salt mines on Google Earth, you’ll notice that they’re real close to the Jhelum River. According to Alexander’s crack team of geography experts, the end of the world was now only about 600 miles away. If he could finish conquering India, he’d have reached his modest goal of conquering the world. But as they marched a bit further, and they heard repors of 300,000 coalition troops sharpening their lances on the other side of the Ganges, his army’s confidence began to wane. But I’m getting off topic. Long story short, Alexander didn’t get to conquer the whole world.

At some point during his coming or going past the Jhelum River, as the story goes, some of the horses from his cavalry started licking the stones, and his men quickly discovered that the stones were salty. And so the salt was discovered in the string of hills known today as the Salt Range. Whether or not this story is true is anyone’s guess. During the British occupation of this region, it was quite the “in” thing to attribute anything and everything to Alexander the Great.

No organized mining is recorded until a millennium-and-a-half later by the Janjua-Raja tribe in 13th century. Given salt’s value in the ancient world, though, once people knew there was salt to be found, they were probably gathering it all along in small-scale operations. In the 16th century the Mughal Empire swept through, led by its first Emperor, Babur.

From the moment he was born, he was destined to be one bad dude, descended as he was from Genghis Khan on his mother’s side and Tamurlane on his father’s side! But again, I’m off on a tangent. Back to the salt mine.

The Mughals made good use of the mines until their empire ran out of steam. The Punjabi Sikhs finally kicked them out and took over the mines in 1809. They’re the ones who named the salt mines “Khewra.” Unfortunately for them, another empire moved in only 40 years later: the British.

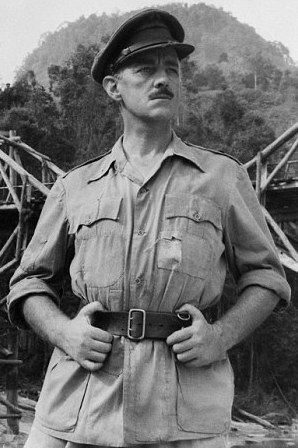

When it came to business, the colonial British meant business. They quickly had it whipped into a shape to run as a proper salt might ought, complete with a good Christian name (it was renamed Mayo salt mine after Lord Mayo, the Viceroy of India), tunnel excavation, and local forced labor.

It was not a nice place to be subjected to forced labor. The workers (men, women, and children) were locked inside and not let out until they’d filled their quotas of salt. In 1876, during a protest, 12 were shot and killed.

It could have been still worse, though, if it hadn’t been for the engineer in charge of the main tunnel. He employed the room-and-pillar method of excavation. Old-fashioned methods often wound up involving just blasting a bigger and bigger cavern until it either collapsed, burying everybody inside, or the mineral deposit ran out. The room-and pillar method deliberately leaves about half of the mineral deposit undisturbed in the form of pillars to keep the cavern’s ceiling from landing on your head. Given that estimated reserves of salt in the Khewra mine run into the several hundreds of millions of tons, and the mine itself produces around 350,000 tons of salt per year, it’ll be a few hundred years before anyone is tempted to start chipping away at the pillars.

After the first world war, heavy equipment began to be used, first in the form of steam engines, and then in the form of electricity, produced by two 500 horsepower diesel generators installed in the 1920s. This modernization brought production into the hundreds of thousands of tons annually. At present, the mine’s tunnel network extends about 25 miles through 19 different levels.

Despite the immense scale, the mine has struggled financially in recent years. In order to try to make the mine profitable, the Pakistani Mineral Development Corporation, which owns the mine, has also been working the tourism angle, with considerable success. I haven’t been there, but it looks to be well worth seeing if you happen to be passing through the Punjab region of Pakistan. Wikipedia estimates the mine receives 250,000 visitors a year. The main shaft has now been converted to a tourist attraction. Some of the highlights are:

…an underground mosque built from blocks of salt,

… a model of the Minar-e-Pakistan (Tower of Pakistan), built from blocks of salt,

… and, of course, a food court.

For the health-conscious visitors, there is a ward with 20 beds for salt-therapy. Many believe that inhaling salt particles in the very sterile environment inside the mine helps with respiratory ailments. Some swear by it, others say it’s quackery. Controversy notwithstanding, it’s certainly affordable. A 2010 article by The Telegraph stated a 10 day treatment costs 42₤ (Currently $52 US). Some critics of alternative health treatment have pointed out that the salt mines are somewhat radioactive. While this is true, the level of radioactivity isn’t much out of the ordinary, according to this research paper.

But beyond the development of tourism, since with withdrawal of the British in 1947, further modernization has, for the most part, ground to a halt.

This article, from the Seattle Times, addresses the plight of miners in the Khewra Salt mine today.

At Asia’s oldest salt mine, the march of technology stopped generations ago. Bare-chested laborers use hand-cranked drills and gunpowder to blast away the pink and orange-colored rock crystal, lucky if they earn a couple of dollars a day…

…Mohammed Buksh works alongside his son Shezad, 24, and three cousins, by the light of a lamp mounted on a gas cylinder. For three years they have been digging the same cavern. It is now about 30 feet high and wide, and 120 feet deep.

Buksh complained that the mine management withdrew mechanized rock-cutting and bore machines in 1998 to save money. The team gets 164 rupees ($2.75) for every ton of rock salt excavated. If they work hard, he said, he can earn about $50 a month — a poor but living wage in Pakistan…

…“The miners are living in medieval conditions,” said Farooq Tariq, secretary-general of the trade-union-affiliated Labor Party of Pakistan. “They have no advantage from technological advancement. They just use their bodies and labor.”…

Muhammed Saifullah Qureshi, the chief mining engineer at Khewra, conceded that little has changed since British times — and that little is likely to.

Speaking inside his colonial-vintage office, complete with a polished desk bell for summoning his secretary, Qureshi said it doesn’t pay to modernize because industrial-grade salt produced worldwide is cheap and the mine has been operating in the red for the past 10 years.

Photo by Luke Duggleby

It’s rather sad when you do the math. When you pay 8 bucks for 4.5 ounces of this salt at Trader Joe’s, the guys risking their necks underground are making a tad over 1/10 of one cent.