Warning: Invalid XML structure returned from Amazon. in /home/sacredvalleysalt/public_html/wp-content/plugins/amazon-product-in-a-post-plugin/inc/amazon-product-in-a-post-aws-signed-request.php on line 946

Notice: Undefined variable: temp in /home/sacredvalleysalt/public_html/wp-content/plugins/amazon-product-in-a-post-plugin/inc/amazon-product-in-a-post-aws-signed-request.php on line 950

Warning: Invalid XML structure returned from Amazon. in /home/sacredvalleysalt/public_html/wp-content/plugins/amazon-product-in-a-post-plugin/inc/amazon-product-in-a-post-aws-signed-request.php on line 946

Notice: Undefined variable: temp in /home/sacredvalleysalt/public_html/wp-content/plugins/amazon-product-in-a-post-plugin/inc/amazon-product-in-a-post-aws-signed-request.php on line 950

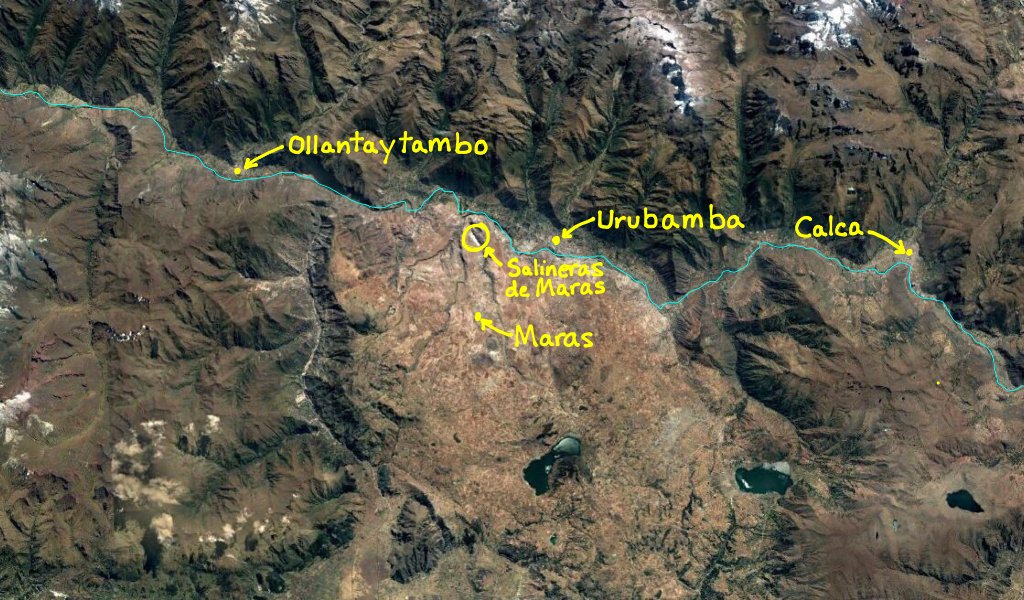

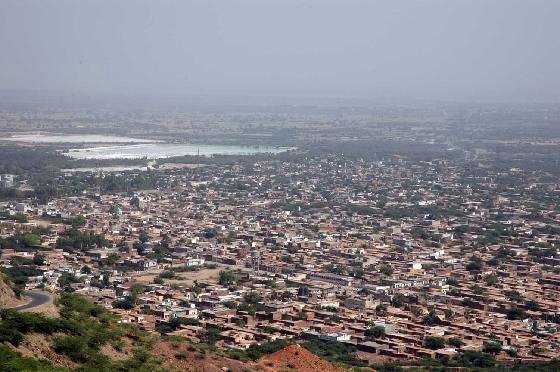

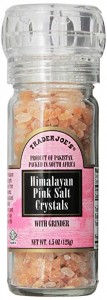

4 pound bulk bag of extra coarse grinder salt from the Sacred Valley near Maras, Peru

Description

This extra coarse salt has been hand sifted to yield a typical grain size of ~0.13 in (3.3mm). It’s meant to be used with a grinder. Comes in a sealed bulk sack.