What do Star Wars and the Sacred Valley have in common?

To start with, I invite you to enjoy this controversial little clip from the original Star Wars episode. If you can set aside you existential angst about who actually fired first, you might notice that the language Greedo speaks in sounds strangely . . .realistic.

This is because he is speaking Quechua: the indigenous language of the Sacred Valley. Quechua actually comprises an entire language family that spreads from Ecuador to Chile. Just like the Romance languages, the Quechua languages have definite similarities to one another, but can only make themselves mutually understood with great difficulty. The form of Quechua spoken in the Sacred Valley is Quechua Cusqueña. (Quechua of Cusco)

You might have heard recently about the fact that many small indigenous languages are slowly being gobbled up by the larger languages of English Spanish and Mandarin. This is absolutely true in the case of Quechua. I came to know numerous families in which the grandparents speak only Quechua, the parents speak Quechua and Spanish, and the grandchildren speak only Spanish. Not only is it sad to see the language itself dying out, but the fact that so many grandchildren are unable to speak to their grandparents puts a human face on problems associated with language transition.

This having been said, it is quite clear that some Quechua words are here to stay. Machu Picchu, for instance, is not just the name of a tourist destination. It actually means “old mountain”. Huyna Picchu (sometimes spelled “Wyna Picchu”) is the smaller mountain right next to Machu Picchu and means, “young mountain.” While most tourists think of these only as place names, Picchu (pronounced peek-chew), Huyna, and Machu are all words frequently heard in everyday conversations.

One of the most interesting things that you will observe in the Sacred Valley is the strange mixing of Quechua and Spanish. If you buy a kilo of potatoes in the market, it is customary to receive yapa, which is a little bit of extra product thrown in after the weight is taken as a show of good faith to the buyer. It is not uncommon to hear people asking for their yapita. This is the Quechua word yapa mixed with the Spanish diminutive suffix ita. The net result is a hybrid word. Most local people couldn’t tell you the origin, but it is universally understood to mean “Hey, don’t forget to throw in a little extra!”

Here is a clip that I filmed from a typical town meeting in Ollantaytambo that contains a typical slurry of Spanish mixed with Quechua.

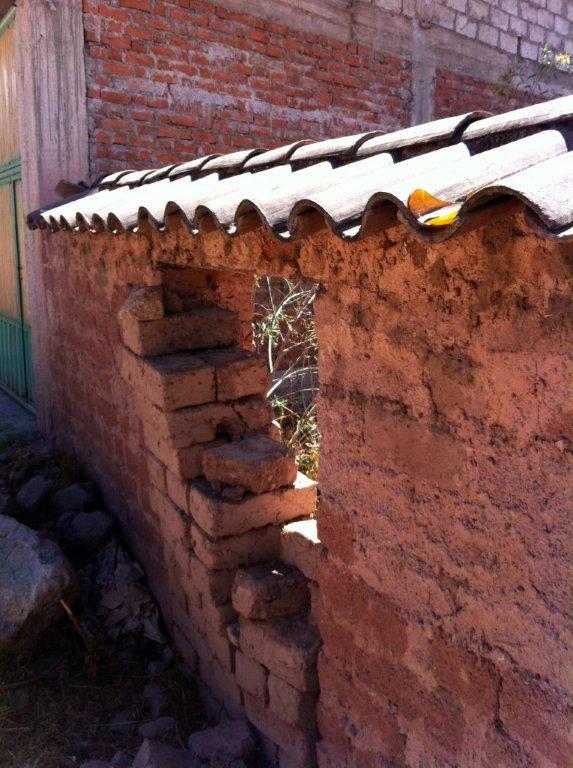

As a tourist, you will be an instant celebrity if you remember to bring miski (candy) to share with children, guides, store clerks, or anybody who you want to make friends with. Wasi is probably the most common word you will see as it means house, and nearly all hotels find a way to include it in their names. Hatun Wasi (the big house), Sumak Wasi (wonderful house), Inca Wasi, and Gringo Wasi are some of the names I have seen. I used to live near a kindergarten called Wawa Wasi (wawa being the word for child).

While the number of Quechua speakers decreases, it is also clear that some words have already been lost completely. I have never met anyone, no-matter how isolated or elderly that knew the Quechua word for the color blue. Nor does modern Quechua have a word for “friend”. The word for brother (huayak’ay) or a modified Spanish loan-word (amigon. depending on the sentence structure) is employed for the task.

To add to the confusion, there is still no consensus on spelling conventions for Quechua. I have seen the word for one with spellings ranging from “huk” to “juj” and many people consider it improper to ever use Spanish loanwords even when no Quechua word or phrase exists that will convey the same idea.

A final, noteworthy result of this recent language transition is the localized deficit of vocabulary. Imagine if every single person that you ever met in your entire life were either first or second generation English learners. It would be very difficult to ever build up an ample vocabulary. The Sacred Valley region finds itself in this very situation with Spanish. Thus, while many children who speak only Spanish, their vocabulary is very limited and they struggle with even basic spelling and grammar.

Here is a welcome sign. It should read Bienvenidos. But since “b” and “v” are pronounced similarly, they are mixed up.